New Bedford fisherman Tony Borges gets useful real-time information from monitoring. For 200 days of each of the past 44 years, Tony Borges has been setting out from New Bedford, Massachusetts in search of groundfish, fluke, and squid. That’s roughly 8800 days for those of you keeping score at home.

He started fishing with his father, though he says his father tried to dissuade him from being a fisherman, instead encouraging his son to join the US Coast Guard. Nevertheless, in 1977, along with his cousin, aunt, and father, he purchased the brand new Sao Paulo. He still owns and operates it today.

For the last seven years, he has also been participating in the Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s Study Fleet. As part of this scientific data collection programme, he records haul-by-haul catch (kept and discarded) information for all species, and he spoke to NOAA greater Atlantic region port agent Bill Duffy about the scheme.

‘When I met Borges early one morning on the Sao Paulo, he was down in the engine room covered in grease – working on his vessel’s first complete overhaul in 40 years. We went to the wheelhouse to talk. He showed me the computer dedicated to running our Fisheries Logbook Data Recording Software (FLDRS), which he uses to record data from each of his tows. He showed me the temperature probe on one of his trawl doors, which collects bottom water temperatures while fishing,’ Bill Duffy said.

Commercial fishing vessels in the Study Fleet collect and report both kept and discarded catch, and bottom water temperature data on every haul. Study Fleet vessels may also collect biological data from their catch when additional data needs are identified by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center scientists. Vessel owners are financially compensated for their participation in the Study Fleet.

Tony Borges likes using FLDRS because he says he knows that ‘the data we put in is accurate.’ He particularly likes the water temperature data.

‘It helps me as a fisherman, since the water temperature at the bottom tells me when I am on fish, and if I move away a couple of degrees, it makes a big difference to what I catch,’ he said.

When he sells the fish, NOAA Fisheries can check his data against the dealer report. NOAA can get information on where the fish was caught, the water temperature data for that tow, and the reported catch for that tow. This provides valuable information to fisheries scientists and managers who evaluate the health of the stocks. They can incorporate data like these into their research and assessments. For fishermen, participating in Study Fleet allows them to contribute quantitative information to scientific research and improve understanding of the northeast’s complex ocean ecosystem.

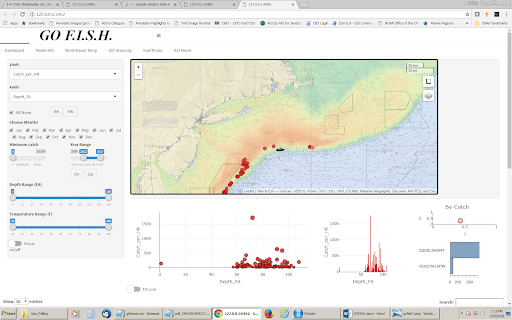

‘We are trying to increase the value of the catch, effort, and environmental data available from Study Fleet fishing vessels. We are working with the fishing industry to develop an application called GOFISH, short for Graphical Offshore Fishing Information System Homepage,’ Bill Duffy said.

‘This system allows commercial fishing captains and vessel owners to map, graph, and analyse the data they have entered through FLDRS. The GOFISH app produces temperature-depth plots, by-catch analysis graphics, and other visualisations that can assist fishing operations. The data remain the property of the vessel owner, but can also be used in research to improve our understanding of marine ecosystems.’

‘Nobody likes it, let’s be honest, nobody likes to be monitored, nobody likes observers,’ Tony Borges replied when asked what he fells about electronic monitoring and reporting.

‘Let us do our stuff out there and monitor us at the dock, make it so you can’t unload without a monitor,’ he suggested.

But he does see the value in collecting scientific data through the FLDRS system.

‘Imagine if we had this data 40 years ago,’ he said.