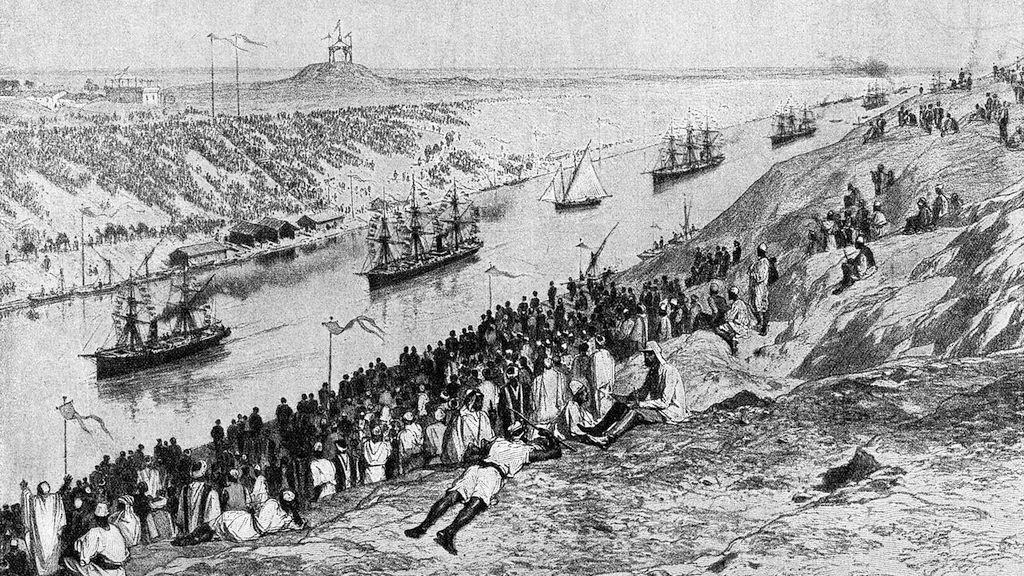

When the Suez Canal was opened 150 years ago, it brought many positive aspects for travel and trade. But it also opened a route for the mass migration of invasive marine species from the Indo-Pacific region, with significant, and generally negative repercussions for the biodiversity of the sea basins concerned.

Pufferfish originate in the Red Sea and are now one of the most harmful invasive species now present in the Mediterranean. The EU-funded LagoMeal project succeeded in developing a commercial fishery for this invasive species that previously had no commercial value.

LagoMeal brought together a team of experts from various national institutions and the private sector. Together they used the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) to develop a process to deactivate a powerful nerve toxin and turn deadly pufferfish into high-quality fishmeal.

Pufferfish, Lagocephalus sceleratus, is a notorious relative of the Japanese fugu, and like its distant cousin, it has no predators because it is highly poisonous. Pufferfish present a considerable threat to the environment and fisheries. An opportunistic predator whose numbers are growing fast, the pufferfish damages fishing gear and catches and preys on native species. Greek fishermen claim that pufferfish damage to their nets alone can cost them each more than €5000 a year.

At the same time, the expansion of aquaculture has increased demand for aquafeed. This puts pressure on the fishmeal supply and fish farmers urgently need new sources of fish protein. Greece currently has only five fish feed production plants, with an annual production of approximately 250,000 tonnes with a value of €300 million. The country’s aquaculture industry currently needs to import a further 50,000 tonnes of fishmeal annually, at a cost of around €70 million.

‘The best way to control an inevitable invasion of an unwanted aquatic population is to create a value for it. By making it valuable you increase the incentive – and the efforts – to collect it,’ said A win-win solution Dr. I. Negas, the project’s scientific lead, explaining that heat-treating the pufferfish removes the deadly toxin, and the project partners believe they could create a profitable market for this otherwise unloved invader. This would in turn provide local fishermen with a new target species, aquaculture producers would benefit from lower feed prices – and pufferfish numbers would fall.

Trials showed that cooking pufferfish at 160°C deactivates the poison to levels safe for human consumption, while at 200°C it disappears. Feeding trials were also encouraging, showing that European sea bass grow well when pufferfish fishmeal replaces up to 30% of conventional fishmeal in their diets.

The project’s business plan looked at a small plant to process 1500 tonnes/year of pufferfish producing 250 tonnes/year of fishmeal and 100 tonnes/year of fish oil. Over ten years the annual return on investment was estimated at 15-25%, depending on the extent of compensatory measures for fishers.

On this basis, processing pufferfish would be an attractive investment for aquafeed producers, and help aquaculture producers reduce costs.The ability to produce local fishmeal with a stable composition, high nutritional value and competitive price could have significant benefits for the industry, and a commercial fishery would help control Lagocephalus sceleratus populations.

EU funding enabled this innovative project to start the process of sourcing alternative protein for fishmeal production, and prove the basic process at lab and pilot scale. The project also helped the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR) and its partners establish connections with the coastal fishing community, gaining trust for future collaborations and research programmes.

Image: Dr. Paraskevi Karachle and Katerina Dogramatzi