The worldwide demand for seafood made a robust post-Covid return, fuelled by the growing demand for high-value seafood in the US, EU, and China, according to analysis by Rabobank.

The soaring demand for fishery and aquaculture products has positioned seafood as the most traded animal protein, with an estimated trade value of USD 164bn in 2021 and a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.44% between 2011 and 2021.

In 2021, seafood trade was roughly 3.6 times the size of beef trade (the second most traded animal protein), five times the size of global pork trade, and eight times the size of poultry trade, signifying the importance of trade for the seafood sector.

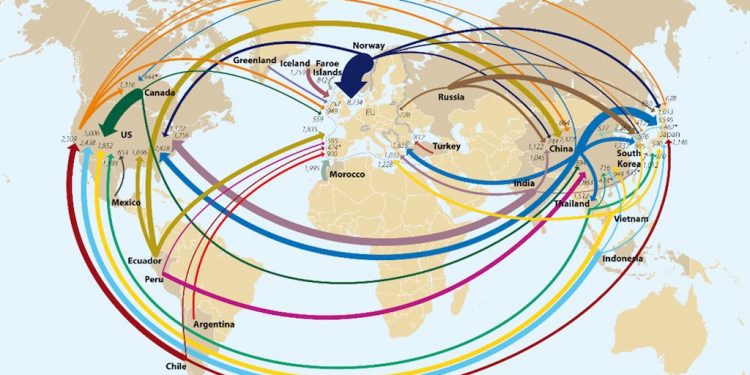

Rabobank’s analysis demonstrates that the global seafood trade is characterised by a broad diversity of products, with each having its own export and import markets.

There are 55 trade flows that are each valued at over USD400m per year and an additional 19 trade flows that are valued between USD200m and USD400m, illustrating the international nature and diversity of seafood trade.

Developing countries play a major role in seafood exports, accounting for seven of the top 10 exporters. Developed countries are increasingly reliant on developing nations for imports of high-value species, especially shrimp from India and Ecuador and salmonids from Chile.

A more detailed look into specific trade flows reveals that trade from Norway to the EU-27+UK retains the top spot, valued at over USD8.7bn and largely comprised of farmed salmon. In second place, there is trade from Canada to the US, valued at USD5bn and dominated by crustaceans (excluding shrimp), which are valued at USD3.34bn. And with more than USD3.3bn worth of seafood in 2021, trade from India to the US comes in third place, driven by demand for farmed Vannamei shrimp, which make up 80% of Indian seafood exports to the US.

The combined imports of the US, China, and EU-27+UK are valued at USD 80bn, roughly 50% of total seafood trade in 2021.

The EU-27+UK remains the largest seafood buyer by value, importing seafood worth over USD 34bn in 2021. However, since 2013, it has grown at a CAGR of only 2%, while in the last five years, the US and China exhibited CAGRs of 6% and 10%, respectively, each roughly doubling the total value of their imports.

US and Chinese Appetite for Premium Seafood Drives Trade Growth

As of 2021, total US seafood imports were valued at USD 28.1bn – a figure USD 8.6bn higher than 2016 total imports – driven by shrimp, salmonids, crabs, and lobsters, which account for 91% of total value added. US demand for premium seafood is visible in its increasing imports of shrimp, salmonids, and crabs, which exhibited value CAGRs (2016-2021) of 7.1%, 10.3%, and 19%, respectively.

In 2021, China’s seafood imports were valued at USD17.2bn. From 2013 to 2021, China’s import volumes exhibited a CAGR of 4.4%, while import values had a CAGR of 10.1%, highlighting the demand shift to more expensive forms of seafood protein. This trend is further evidenced by the strong rebound in imports in 2021 that followed the initial Covid-19 lockdowns and added USD2.4bn compared to 2020. This growth was driven by shrimp, fishmeal, crabs, and salmonids, all of which exhibited high double-digit year-on-year growth and together accounted for 94% of import growth.

High-Value Species Will Drive Seafood Trade Growth

Since 2013, the winners of global seafood trade have been high-value species such as shrimp and salmonids, which exhibited volume CAGRs of 6% and 2% and value CAGRs of 3.3% and 2.8%, respectively. During the pandemic, higher-value proteins such as beef, shrimp, and salmonids outperformed other proteins, with year-on-year growth in trade value of 16%, 17%, and 20%, respectively.

Rabobank’s analysts expect sustainability and demand for healthy and premium species to continue driving trade volumes of high-value seafood in the coming years, and exporters such as India and Ecuador are well positioned to capitalise on emerging trends and close the gap in the exporter rankings.

‘We are also seeing unprecedented high prices for many seafood species due to challenges in international trade such as rising freight and energy costs and continued lockdowns in China,’ they state.

‘However, recent data suggests the impact on seafood demand may become material, especially if a recessionary environment develops in the second half of 2022 or 2023. This could affect seafood market prices and the value of trade flows. To conclude, seafood is not only a healthy protein important for food security, it also a key export commodity for many developing nations and a source of employment for millions of people.’