The historic castles, churches and pastel-coloured port towns lining the shores of the small volcanic island of Procida in the Bay of Naples have earned it the award of the 2022 Italian Capital of Culture. But it’s the rich and dynamic marine ecosystem hiding underwater off the island’s coasts that has made it the site of a unique and innovative effort in a different kind of culture – aquaculture.

This is this growing sector that drew the General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean’s aquaculture team to Procida this summer, to complete a field visit to the sea urchin aquaculture sector and to collect materials and conduct underwater research in order to launch a pilot action on sea urchin restocking.

‘Sea urchin farming is a new activity that combines innovation with the restoration of ecosystems. As such, it must be well studied and thought out so that models can be proposed for the Mediterranean region,’ said Houssam Hamza, GFCM Aquaculture Officer.

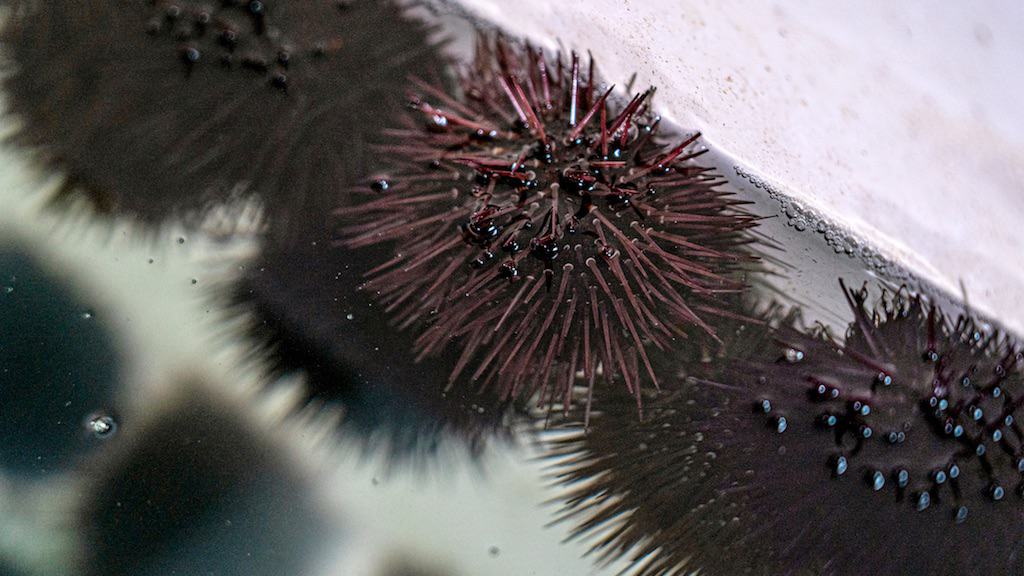

The purple sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) is considered to be one of the most important herbivores in the Mediterranean Sea and is a famous culinary delicacy in many countries. As one of the organisms defining the ecological system in the region, P. lividus has long been used as an animal model in developmental biology and as an indicator in the assessment of environmental quality.

‘This species is very important for ecosystems, because it transfers energy from primary production, i.e. from plants, to other ecosystems, and it is also fundamental for scientific research, as it has a very special embryo that makes it possible to carry out research on evolution and development,’ said Valerio Zupo, Senior Scientist at Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples.

Contrary to what their robust appearance may suggest, sea urchins are very sensitive to environmental conditions, especially in the early stages of life, and they require intensive monitoring and special attention during the production process. The overall status of the sea urchin populations in the Mediterranean is of concern. As a precaution pending formal stock assessments, sea urchins should be considered in need of conservation due to the impacts of fisheries and climate change, among other factors. Nevertheless, their numbers, spread and impacts vary depending on local conditions and harvesting.

Given the importance of the species as a resource for fisheries and the key role it plays as a macroherbivore, regulating the volume of algae and helping to maintain balance in the ecosystem, the GFCM’s pilot action aims to support effective and innovative restorative aquaculture practices as a solution to revive the sea urchin’s populations.

Within this pilot project, the GFCM is working to support and advise aquaculture enterprises that are involved in the production and restocking of sea urchins in the Mediterranean and Black Sea region. One of these is Echinoidea, a small-scale aquaculture facility in Procida, that was established in 2016 by Michele Trapanese, who manages the farm with his two children, Chiara and Filippo. Echinoidea combines business with conservation to achieve trailblazing advances in the production of farmed sea urchins, which are valued for their delicious roe, and in the restocking of sea urchin populations in the area.

‘It’s important and meaningful for me to participate in this project which is all about environmental protection, sustainable fishing and green economy,’ said Echinoidea administrator Chiara Trapanese.

The farm produces urchins in a closed recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) and was successful in leading preliminary experiments of artificial fertilisation and rearing of sea urchins in collaboration with the research institute Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. Following the collection of mature urchins in the Gulf of Naples, female and male gametes are extracted from individuals selected for in vitro fertilisation in the laboratory, and the juveniles obtained are placed under continuous surveillance and controlled rearing conditions (temperature, water quality and feeding) over the course of the entire production cycle, which usually lasts about nine months. Once the adults are ready, they are released back into their natural environment to continue growing in an area specifically intended for aquaculture.

Although the Procida pilot project still requires further development and co-ordination with stakeholders, it has the potential to become a model case study for echinoculture that could be expanded across the Mediterranean Sea.

‘In Procida, we are experimenting with new forms of aquaculture. Sea urchin breeding is certainly an innovative activity that fits into the strong mussel farming tradition of our region,’ said Nicola Caputo, counsellor for agriculture at the regional government of Campania.

To this effect, the GFCM organised a seminar on 4th October in Procida in collaboration with the Centre for services, assistance, studies and training for the modernisation of public administration Formez PA, the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies (MIPAAF) and the regional government of Campania.

Among the participants were local authorities, representatives of administrations and small-scale fisheries, fish farmers and researchers, as it set out to be a moment of collective discussion on the challenges and opportunities that these sustainable aquaculture activities can represent for the sector, the protection of the sea and the environment, diversification in fish food production, and the possibility of bringing additional benefits to local communities.