Fisheries consultant Ross Winstanley is planning to take part in the 8th World Recreational Fishing Conference later this year to present the idea concept of consumers as stakeholders – drawing on the decision by the government of the Australian state of Victoria to close a sustainable net fishery to replace it with a solely recreational fishery.

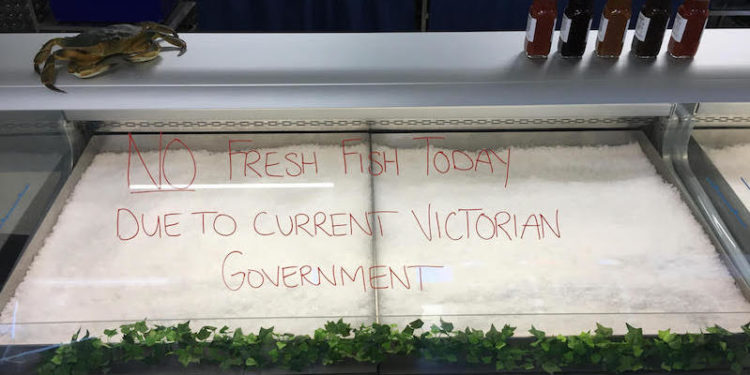

‘The 2014 Victorian Government decision to remove a proven sustainable commercial net fishery in Port Phillip Bay is disenfranchising five million Victorian consumers in order to benefit perhaps 100,000 regular anglers who already enjoy enviable fishing,’ he said.

‘The political decision process took no account of 20 years of State-funded stock assessments all of which demonstrated that commercial and recreational fishing, combined, continue to be sustainable. No advice was sought from the statutory Fisheries Advisory Council, established to provide balanced advice on such policy issues.’

He comments that the proposal to float the concept of consumers as stakeholders is based on the concept of fish stocks being a publicly-owned resource and therefore it follows that domestic consumers of locally-caught seafood should be recognised as primary stakeholders in resource allocation processes.

‘For any stock that is fished commercially to supply domestic markets, local consumers generally form the largest stakeholder group. Further, in terms of numbers, they roughly equate to “the community” – the owners of the resource. Why then are they not ranked in equal terms to recreational, commercial, aboriginal, subsistence and artisanal interests in relation to recognition of “rights” and a clear position in allocation policy processes?’

‘Too often, governments are prepared to terminate demonstrably sustainable commercial fisheries in favour of recreational fishing when the overall community benefits from both sectors are perfectly sustainable. Too often, on-water conflicts between anglers and commercial fishermen are “resolved” by eliminating commercial fishing instead of seeking negotiated resolutions or drawing on the range of fisheries management tools. Too often, commercial fishers must accept publicly-funded compensation packages to quit sustainable fisheries. Sometimes, compensation packages are funded from recreational fishing licence revenue; this effectively reduces resource allocation to a commercial transaction between commercial and recreational fishers.’

He points out that in these conflicts the usual contestants have advocacy groups that lobby hard for their interests – while domestic consumers tend to be short of representation – and they are totally unaware that their access to community-owned, i.e. their resource is being negotiated away through processes in which they have no part.

‘In theory, consumers should be able to rely on their elected representatives to recognise and protect their interests. However, in practice governments respond to strident lobbying and consumers are quietly consigned to alternative seafood sources. Consumers are, thus, excluded from what may otherwise be quite legitimate decision processes.’

‘At no time did the Government consider consumers’ interests in the fishery or consult with the broader community, nor did it explain why the community should not continue to enjoy the combined benefits from commercial and recreational fishing. All in all the Government seems to have abandoned one of the key objectives of the Fisheries Act 1995, namely to promote sustainable commercial fishing ..for the benefit of present and future generations.’