VisNed and a number of fishing vessels are behind the development by Dutch researchers and fishermen of a digital tool to implement a fully documented fishery (FDF), with support from the EU.

There are requirements that all catches to be registered and landed. But this requires time and space and can be very costly. VisNed calculates that, on average, a vessel would need around four more people on board to process and land the unwanted catches. However, for reasons of space and economy, it is not practical to operate with larger crews.

This is the point at which science and fisheries intersect to develop innovative solutions. In the Netherlands, researchers at Wageningen Marine Research and Agro Food Robotics, in cooperation with VisNed and several fishing vessels are developing a digital tool to implement a fully documented fishery (FDF).

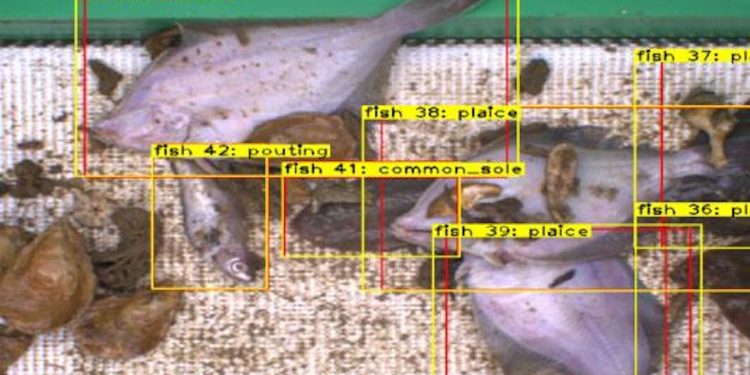

FDF introduces automated recognition of the size and species of each fish, distinguishing between catches fit for human consumption (above minimum size) and unwanted catches (below minimum size). Using remote electronic monitoring (REM) systems, the tool can determine the weight of the total catch.

Developed by Agro Food Robotics, the process uses complex algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI) and spectral learning and vision technologies to recognise fish species and classify the fish by size (above or below the allowed minimum conservation reference size). The same technology is already in use for measuring and assessing the quality of agricultural products, such as broccoli and tomatoes.

To test the process in a life-like environment, researchers at the Den Helder fish market first constructed an exact copy of a fish sorting line used on board fishing vessels and equipped it with two high-definition cameras: one to recognise the species and one for 3D visualisation and determination of volume.

After a successful trial run, the prototype was then tested on board a fishing vessel for the effects of vessel movement and salt-water spray on the camera lenses. The second trial with more vessels at sea was launched in 2021.

Preliminary results indicate that the process can be applied without major changes to the way fish is normally handled on board. It currently recognises four species – plaice, sole, turbot and brill – with speed and accuracy. The technology calculates the weight of each fish by determining its volume and can also distinguish if a fish is above or below the minimum size.

An earlier project (Innoray) has demonstrated that the same technology can be used to distinguish between the three main commercial species of rays, even when they are lying upside down – which is very difficult for the human eye.

The project also meets privacy and data protection (GDPR) requirements, as the system can process data without human interaction. In fact, the footage can be destroyed as soon as the computer has counted the fish and the data belongs to the fishers themselves.

A great deal of potential is seen in this technology. Cameras could be linked to electronic catch reporting systems (e-logbook) and reduce the administrative burden on the skipper. It also allows real-time monitoring of fishery, which could improve data collection and transparency.

Because it collects data on catch quantity and composition of both target species and unwanted catches, this technology could also become an important source for scientists evaluating the state of fish stocks, boosting the efforts for the sustainable management of marine resources.

While the project is yet to be fully evaluated, the FDF technology could become a mainstay of EU and global fisheries, all of whom are facing the same challenges of registering catches by species and size. The project received just under €3 million in support from the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF).